"I was in a concentration camp and I didn't know what was going on...We did not believe it because it is not human nature to kill people. How could we figure out they were going to kill hundreds or thousands or millions of people?" -Luba Malz

Luba Dora Malz

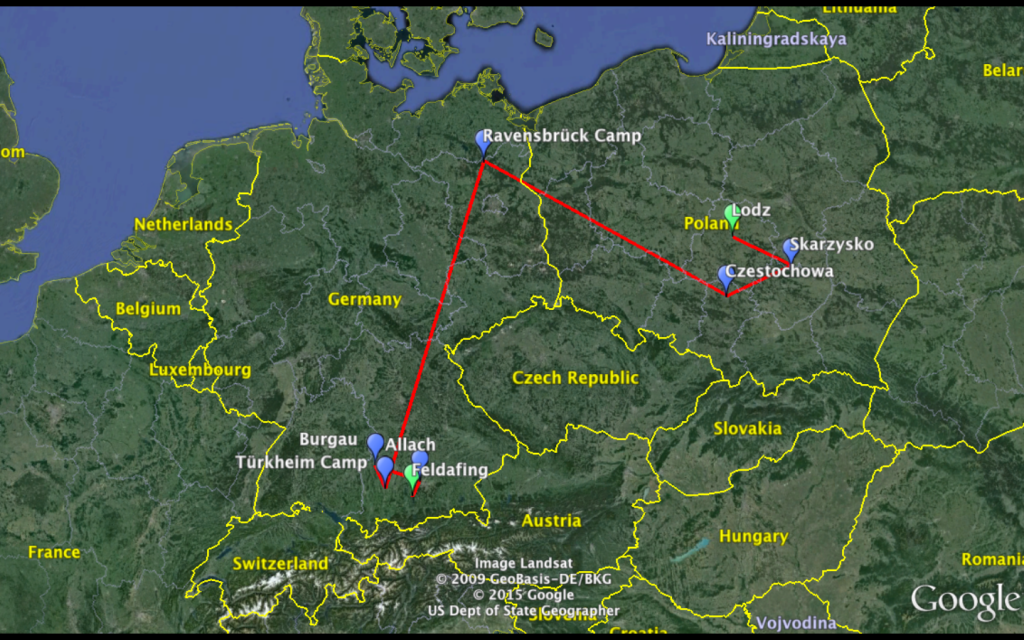

When the Germans invaded Poland, Luba Dora Malz (née Rogozinsky) was 13 years old. She was born in Lodz, Poland in 1926. The first indication to Luba's family that something was wrong is when Jews in Poland were no longer allowed to go to school. Jewish owned factories began to be closed down. That is when the war started for her family.

One night, a neighbor identified her as Jewish when she went into a nearby store to pay for bread. Luba was kicked out of the store without the bread. She was then beaten. That same neighbor was a close family friend and their children had played with Luba and her siblings.

Lodz Ghetto

The ghetto that she first went to in Lodz was the size of a small town, with thousands of people. Each apartment housed multiple families. While in the ghetto, she made candy from sugar and sold it to others. She used the money to buy bread. They were always hungry and people in the ghetto began fighting. One day, she recalls seeing a mother throw her child out the window because the child was begging for food. The mother didn't have any and, tragically, became so irritated. Many people killed themselves. "People around were dying like flies," Luba recalls. Some people would even keep their dead family members in the house in order to obtain the deceased person's food rations in addition to their own. They did not report deaths for fear of loosing the potential rations.

They saw people being deported, but they did not know what was happening. They thought they were being taken to work in fields, or kitchens, or other places where they were needed.

Forced Labor and Dora's Courage

The Lodz ghetto: "People in the ghetto were dying out, so they brought more people" -Luba Malz

Dora was taken to the town of Skarzysko for about 6 weeks, where she lived in bunkers. In the middle of the night, she was transferred to the town of Czestochowa. Her assignment there was in an ammunition factory where she would check for defective bullets as they passed down on a conveyor belt. One time, she accidentally missed a defect, and when the Germans discovered that she had missed a defective bullet, she was whipped 100 times across the back.

"They took me to the barracks and they beat me. My back was like a mop. I had to take care of myself; there was nobody there to take care of me."

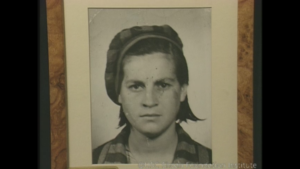

Luba at age 19, just after being freed:"I was a healthy child, but when I started going from one concentration camp to another, the health wasn't there anymore"

Luba and a few other women in the barracks heard that the factory in Czestochowa was going to be bombed by the Soviet army, and anybody there would be killed. She and a few others tried to run from the factory, but were caught by German soldiers. They were put on a cattle car without food and sent to the Ravensbrück camp just north of Berlin. The trip took a few days.

"I saw the crematorium boiling. We used to ask 'what smells?' Must be the kitchen.'"

She was tasked with taking wagons full of bodies to the crematorium. She thought that because there was such a limited supply of food, people would die from hunger and because there were so many deaths, it was easiest to just cremate the bodies. Everybody was given a number. In Ravensbruck, she was tasked with pulling out tree roots after trees were cut down. Some people resorted to eating the roots that they had pulled. From Ravensbruck, she was taken to a small German town. She and the other prisoners were given pots to get soup. Meanwhile, the German soldiers gave the German children sticks and taught them to beat the prisoners. As soon as a prisoner would go to get soup, while standing in line, children would beat them with sticks. Many people, including Luba, dropped their soup in the process of being beaten and were not able to eat.

After Ravensbruck she was transferred to Türkheim in southern Germany. She again lived in barracks. In Türkheim, her job was to sort out clothing. She was not told where the clothes came from but she knew that they were from the people who were burned in the crematoriums. One night, she was carrying coffee and the ground was slippery, so she could not move fast. Meanwhile, a German girl was harassing and beating her. "She was kicking me till I got very mad, and I put down the coffee, turned around, and grabbed her head and hit her and kicked , I must have left her dead." She was in Türkheim for a short time before, in the middle of the night, she was loaded onto a truck with other prisoners and taken to the town of Burgau. In Burgau, there were no other Poles, so Luba became friends with Hungarians who were at living with her. She was then taken to the Allach concentration camp. She went days without food. After seeing mountains of dead bodies, she and became convinced that no prisoners would survive. "I didn't even know where I was and which place they took us. Sometimes we even forgot the date." They only knew the season. She says that it was impossible for her or any other survivors to remember accurately how long they were in each location. Every morning, the prisoners would stand outside and the German guards would take those who did not look healthy. Luba thought that the selected people were just being relocated, but she then realized that they were being killed.

Death March and Liberation:

One morning in Türkheim, she was forced to march in groups of twenty five; each group being followed by an armed German soldier. It rained day and night and the march lasted a few days. She did not know where she was being taken. She and hundreds of other prisoners were marched into a huge grave, and the Germans were standing above watching them. All of a sudden, the soldiers began running away. Despite the prisoners essentially being free, none of them were strong enough to pull themselves out of the grave. She soon found out the German soldiers were running away because American soldiers were approaching. When the Americans arrived, they took the prisoners out of the mass grave on stretchers. Luba was taken directly to the hospital because she was sick with Typhus. An American woman came to her in the hospital and asked her if she wanted anything. Luba asked simply for a lemon, but because of the language barrier, it was difficult to communicate with the Americans. She was then sent to another hospital near Garmisch, Germany. While in the hospital, she met her future husband, Nathan Malz.

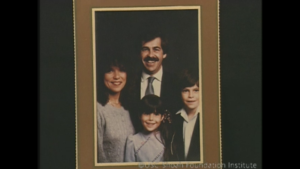

After living with her new husband in a displaced persons camp in Feldafing, Germany, she wanted to go to Israel, but she was told that there was no work in Israel. She went to America with her husband and their newly born son, Morris, afterwards. Her husband got a job in New York City and they rented an apartment. She got a job in a suit making factory. She found out that one of her sisters and a brother survived the Holocaust and were living in the Soviet Union. Her husband wanted a big family, but her doctor said that she is only strong enough to have two children. She had another child, Abraham, when her first son Morris was five years old. Her husband learned how to make shoes in the ghetto back in Europe, so he got a job in the US making shoes and other leather products. Her husband did not want to talk about his experience, and he did not want to hear Luba's experience. He had many horrific nightmares. Her husband Nathan died in 1975. Luba eventually found her way to Staten Island to live with her son Abe, a professor at the College of Staten Island, and his family. She passed in 2003.

A map of Luba's locations during the Holocaust starting in Lodz, Poland and ending in Feldafing, Germany

For Further Reading:

Benz, Wolfgang, and Barbara Distel, eds. Dachau and the Nazi Terror. 2nd ed. Dachau: Verl. Dachauer Hefte, 2004.

Berben, Paul. Dachau, 1933-1945: The Official History. London: Norfolk Press, 1975.

Berenbaum, Michael. “Dachau.” In Encyclopedia Britannica. N.p.: n.p., 2014. Accessed April 18, 2015. http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/149394/Dachau.

“Dachau.” ushmm.org. Last modified June 20, 2014. Accessed April 3, 2015. http://www.ushmm.org/wlc/en/article.php?ModuleId=10005214.

Einwohner L. Rachel, (2009) The Need to Know: Cultured Ignorance and Jewish Resistance in the Ghettos of Warsaw, Vilna, and Lodz. The Sociological Quarterly,Vol. 50 No.3.

Friedländer, Saul, and Orna Kenan. Nazi Germany and the Jews, 1933-1945. New York: Harper Perennial, 2009.

Gould Gillian,(1997) Religious life in the ghettos Warsaw and Lodz, , The journal of progressive Judaism 7.

Isaiah Trunk, (2006) Lodz Ghetto: A History, Indiana University Press: Bloomington and Indianapolis

Kassow Sammuel, (2007), The Case of Lodz: New research of the last ghetto, , Volume 35: Issue 2.

Lyons, Michael J. World War II: A Short History. 3rd ed. Upper Saddle River, N.J.: Prentice Hall, 1999.

Malz, Luba. Interview. Visual History Archive. USC Shoah Foundation. Staten Island: 1997. Web. 18 Nov. 1997.

Suderland, Maja. Inside Concentration Camps. Translated by Jessica Spengler. English ed. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press, 2013.

Yahil, Leni. The Holocaust: The Fate of European Jewry, 1932-1945. New York: Oxford University Press, 1991.

Yosef Zelḳoṿiṭsh, Michal Unger,(2002) In Those Terrible Days: Writings from the Lodz Ghetto, Jerusalem: Daf Noy

Student Authors:

Maria Meskhi and Adam O'Brien