The only student newspaper for virtually every living Wagner alumna and alumnus was The Wagnerian, first published Nov. 8, 1934. But for one brief period in 1964-65, there was another student newspaper on Grymes Hill: The Observer.

Despite the coincidence of timing, The Observer was not inspired by the well-known Berkeley Free Speech Movement, which swept the University of California’s flagship campus that year.

No; it arose from students’ aggravation at the college’s quashing of a calendar of campus events developed independently of The Wagnerian.

“At that time, The Wagnerian was produced using a hot-type letterpress,” Mark Anderson ’69 told us. “It took three or four days to get the thing out.”

Because that lead time made it sometimes impractical to publish a listing of upcoming events in The Wagnerian, the paper’s production manager decided to publish something small and low-tech on his own: a single-page, weekly, mimeographed newsletter called The Grapevine.

Unfortunately, doing so violated a school rule that all publications be approved by the administration — so The Grapevine was summarily shut down after its first and only issue.

Several weeks later, a few students irritated with the college’s heavy-handed response came back with another mimeo newsletter, a two-pager called The Grape. In addition to descriptions of upcoming events, The Grape contained editorial comments on college operations.

Again, the college shut it down after just one issue.

Again, the college shut it down after just one issue.

Adding to the indignation over student censorship was The Wagnerian’s rejection of a satirical (and very popular) “final examination” for a mandatory religion course. The first question gives a good indication of what the “test’s” 18 multiple-choice queries looked like:

One of the still-existing traditions of the ancient Hebrew religion which has been described as a health law is: (a) not eating on the Sabbath, (b) not eating in the Hawk’s Nest on the Sabbath, (c) not eating during chapel hour, (d) not eating in the Hawk’s Nest.

One group of students decided they’d had enough.

Wagner College needed an underground newspaper, they said — and Mark Anderson should head it up.

Mark, you see, knew something about how things were printed. His father ran a company that specialized in publishing corporate annual reports, so printing was in his blood.

One factor, however, gave Editor Mark pause: the college’s prohibition of such publications.

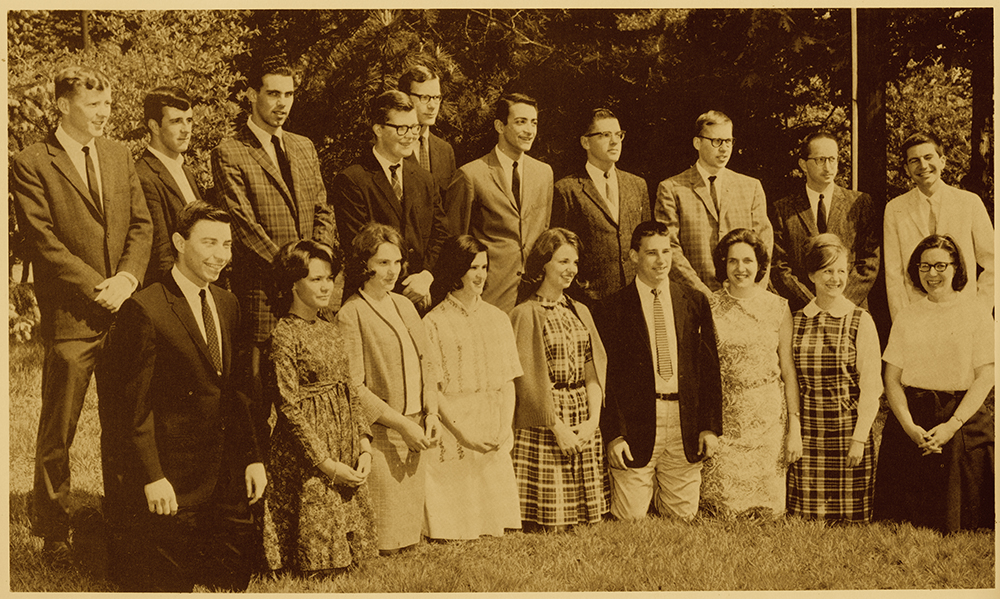

When the first issue of their underground paper was published, pen names were used for everyone involved. Even the front-page photo of The Observer’s staff was taken from behind so that nobody’s face was shown.

The first issue — Dec. 16, 1964 — made an impact.

But it wasn’t until April 1965 — when The Wagnerian was put on hold while the college’s Publications Board addressed some editorial questions — that The Observer really came into its own … real names, and all! For a couple of months, Wagner’s underground newspaper was its only newspaper.

And then … as quickly as it appeared, The Observer was gone after just five issues in print.

* * * * *

After editing The Observer, it took Mark Anderson a few more years to complete his Wagner degree.

“One of the last courses I took was an elective, Business Law, taught by an old warhorse lawyer,” Mark recalled. “Everyone else hated that course, but I enjoyed it, and it occurred to me that maybe this was something that was right for me.”

When the course was over, Mark asked the professor what he thought about his idea of attending law school.

“Absolutely,” the professor told Mark, “you’re a natural” — and, apparently, he was right.

A law school course on land use set Mark on his career path.

“By the time I got through law school,” Mark said, “I had a pretty good idea of where I was going: I wanted to work for a small office. I wanted to be in a growing area of New Jersey — which seemed like Somerville, at the time. And I wanted to do land use.

“I took a job here [at the firm of Woolson Anderson Peach, in Somerville], and I’ve been with the same firm, through several name changes, since 1972.”

Somerville, the seat of Somerset County, is just a stone’s throw from Mark’s hometown of New Providence, New Jersey, where his father had served for a dozen years on the local school board. The only sheepskin hanging on the wall in Mark’s office is his junior high school diploma — signed by his father, who was then president of the board of education.

“I was raised to value public service,” Mark said, which is one of the reasons he is so proud that his firm represents several nearby municipalities and local land-use boards.